Opening arguments

Before you know it, LA’s opening ceremonies will be here — but they’re not going to be where most Angelenos will expect them to be.

LA needs a plan

During the last session of last Friday's Move LA conference, the mainstage presentation on affordable housing was virtually empty. Instead, the majority of the attendees were packed into a Being John Malkovich-esque half-space under the ballroom with low ceilings, no natural light, and musty AC bellowing out the vents. Each of us had bravely ventured into the bowels of the Biltmore Hotel to see a breakout session entitled "What Will Be the Legacy of the Olympics & Paralympics in Los Angeles?" And the setting was, in many ways, the perfect metaphor for what was happening in above-ground LA.

"Being in a windowless basement room that smells a little dodgy is definitely how it has felt to be working on the Olympics for the last couple of years," said Metro's chief innovation officer Seleta Reynolds. "The biggest challenge has been to get people to really understand the complexity of it, and also understand how it presents an opportunity for us to think differently about how we work together."

Clearly the topic had the full attention of the Move LA crowd huddled underground — dozens of bold-faced names from throughout the region working on transportation, housing, and climate. But Reynolds said it had been difficult to get officials to understand that the window for making legacy improvements was swiftly slamming shut. Anyone who regularly watches Metro board meetings — shout out to all 37 of us — will recognize that Reynolds, one of a handful of people in local government to be working full-time on the 2028 Olympic and Paralympic Games, has been consistent in this messaging. "There's nothing magic that happens just because you host an Olympic games," she said Friday. "It's a moment in time that you can take advantage of or not. It's going to happen either way."

I was excited to hear, after many months of receiving questions about this very topic, how exactly the city of LA was planning to take advantage of this moment. But instead, the city was sounding its own alarm.

"The cavalry is not coming," said Erin Bromaghim, LA's deputy mayor of international affairs, who was seated next to Reynolds on the panel. "We, the collective we, in this room are the cavalry. If you have a great idea for something that you'd like to see happen, and you want to use 2028 as either the debut or the time to deliver that, or whatever, let's do it."

Wait. The Olympic legacy improvements are up to... us?

"LA28 is not going to come and drop you on the head with their fairy wand," continued Bromaghim, who served a similar role in former mayor Eric Garcetti's administration. "That's not happening. The city, for our want of capacity, is likely not to be able to do that either."

She's saying this, by the way, with LA28 representatives sitting right there in the audience.

The tone of Friday's conversation was a marked departure from the LA28 pep rally I'd attended in April, just after LA Mayor Karen Bass and other LA city leaders had returned from a trip to Paris. "I led a delegation to Paris because we didn't want to wait for the games to start to find out how they in Paris were preparing for this event," said Bass, standing on a stage in Expo Park, the flame from the previous games flickering behind her atop the Coliseum. "And that same attitude of urgent preparation is what we are doing here today."

"Urgent preparation" would accurately describe what Metro, the other government entity that Bass currently leads, has been doing. When LA got the games, Metro approved a list of projects the agency wanted to complete by 2028. When it was clear that many of those projects would not be completed by 2028, Metro started making a new list, whittled down from 200 projects, prioritized by equity metrics, feasibility, and potential funding sources. Metro solicited community feedback on that list, while publicly sharing its goals and vision for 2028. Here's one Olympic-related goal: "Enable all ticketed spectators and workforce to travel to Games venues by public transit, walking, or cycling. Ensure accessibility for all."

But despite the fact that we finalized our games agreement with LA28 in 2021, LA still has no strategic document for what we want to do as a city by 2028.

LA needs a plan.

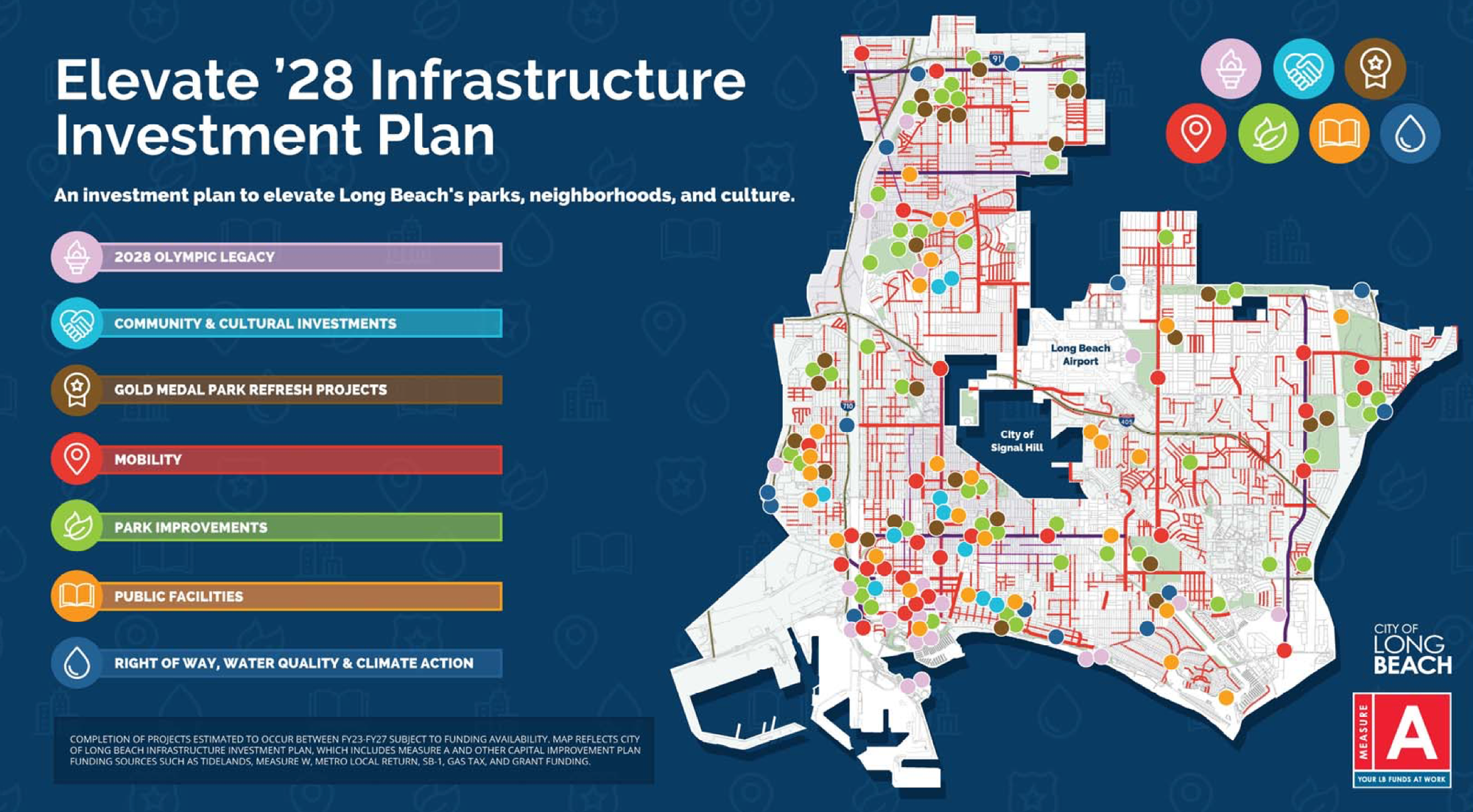

When it comes to vision, other places where Olympic activities will be happening have been kicking LA's butt. In May, the city of Long Beach signed an agreement with LA28 to host some events including BMX, rowing, and open water swimming. But last year, long before that agreement was signed, the city approved a $758 million capital improvement plan named Elevate 28, a list of 180 public works projects scheduled to be finished before the games. It includes everything from sidewalk widening to stormwater medians, 25 "gold medal" park renovation projects, and improvements to public buildings like fire stations and libraries.

Unlike LA's "no-build" venues, Long Beach did need money to make venue improvements; about $187 million of Elevate 28 is allocated to infrastructure for hosting events. But the rest of it goes to everyday improvements, with a focus on underserved neighborhoods in the western part of the city. "The Olympics are coming in 2028," said Long Beach Mayor Rex Richardson in February, "but these aren’t necessarily Olympic facilities."

LA County is taking a different approach. Last month, the county government laid the groundwork for creating a community benefits agreement for the Olympics. A motion co-sponsored by Supervisors Holly Mitchell and Hilda Solis aims to assess the potential impact of the games and mobilize efforts to prevent displacement, complete key legacy transportation projects, and set up a revenue generator that would fund public improvements for the highest-need communities. "The broader region will share the limelight and responsibility of being on a global stage," Mitchell said in a statement. "This is about ensuring we are prepared for the additional support our constituents will need and can maximize the economic benefits the games bring."

Aside from getting a full analysis of the positive and negative impacts of the games — something I don't see the city of LA ever commissioning — what the county's motion could also end up doing is establishing a set of goals for 2028 that other cities can align themselves with. In the absence of the city of LA's leadership, this is going to be greater LA's best shot at setting collective regional priorities — something that's desperately needed before the games come to town.

This newly announced LA strategy for 2028 — urge the community to do the heavy lifting and call the mayor's office when you're ready to promote it — might sound good in theory, like we're producing the ultimate grassroots games. On the panel was Jason Foster, president and COO of Destination Crenshaw, probably the best example of a community-driven legacy project: a $100 million Black cultural corridor that threads 1.3 miles of Crenshaw Boulevard with public art, parks, and hundreds of new trees. "I think the only reason everybody south of the 10 is not vehemently against the Olympics is because this project started 10 years ago," he said Friday. But Foster says projects like this still need more guiding strategy from the city. "I think that what we did can happen in other communities," he said. "But I think it helps if our public municipality pushes them forward, and doesn't rely on the community to actually bootstrap it."

One thing that would help, he said, particularly with procuring funding from outside sources, is showing how projects like Destination Crenshaw fit into a larger citywide plan. "If LA has a capital improvements plan, we have it all written out," he said. "That elevates and shows where the funding is being spent, it actually builds confidence that it's happening."

The kind of plan Foster is talking about — and I've seen him speak very passionately about capital planning at UCLA's Luskin Summit — is what the city needs to prepare in advance of 2028. It's what Metro does. It's what Long Beach does. There's even solid LA precedent: Destination Crenshaw happened because it's in the district of LA's next council president, Marqueece Harris-Dawson, the only council office with a capital planning department. But right now, unlike every other major U.S. city, LA as a whole only budgets one year at a time, and, therefore, can't properly plan for long-range capital improvements. The Olympics aren't going to change that. But you know who could? Mayor Karen Bass. "We're just going to out-think ourselves if we don't think about the material change that we want to happen," said Foster. "We have the ability, but what's the plan? And what's the human, qualitative thing we're going to leave behind?"

As Bromaghim noted, LA's Olympics technically start the day Paris's Olympics ends: August 11, 2024. By the end of this panel, I think everyone in our little bunker was mentally already there. The session's moderator, Hilary Norton, executive director of FASTLinkDTLA and a transportation commissioner for the state of California, tried to wrap it up on a positive note. "If we didn’t already have the wakeup call," she said, "today is it!"

The next four years are going to be a wild ride.

LA needs a plan. 🔥