Confronting LA's park crisis

LA's Park Needs Assessment provides a roadmap — or perhaps a well-shaded, native-planted pathmap? — for a department that's been asked to do more and more with less

On a sticky summer evening like last night, the essential role of Los Angeles's parks cannot be denied. At sundown, grassy lawns are dotted with families seeking a physical respite from their steamy apartments. Teens tap out kick flips in the skate plaza, seniors slowly stroll in the lengthening shadows, a pickup basketball game resumes as it gets dark. The rec center sends home the last student from its after-school program, highly subsidized for working parents, and assumes its job as one of the city's official cooling centers. Maybe there's a pool where a councilmember scraped together enough discretionary funds to stay open past Labor Day. As the sun finally sets, it's clear that parks are more than playgrounds and pickleball — they're literally the frontlines of LA's emergency response.

Now consider that LA's park system operates with about half the full-time staff it had two decades ago, managing over 500 sites and 16,000 acres of green space as the department's deferred maintenance balloons over $2 billion. The city is demanding more than ever from our severely underfunded parks and the hard-working public employees who run them.

And right now, says Jimmy Kim, the general manager of LA's Department of Recreation and Parks, it's all just barely holding together.

"I always say we're great with duct tape," he told me. "We kind of mend things to make it work."

Over the last eight months, a supergroup team led by the landscape designers at OLIN has attempted to envision an entirely different LA — where public space is a priority. They visited all 489 LA city parks, conducted dozens of outreach meetings, and surveyed thousands of park users. Their draft recommendations for how the city can get there are out this week, as part of LA's Park Needs Assessment — the city's first such assessment in 15 years.

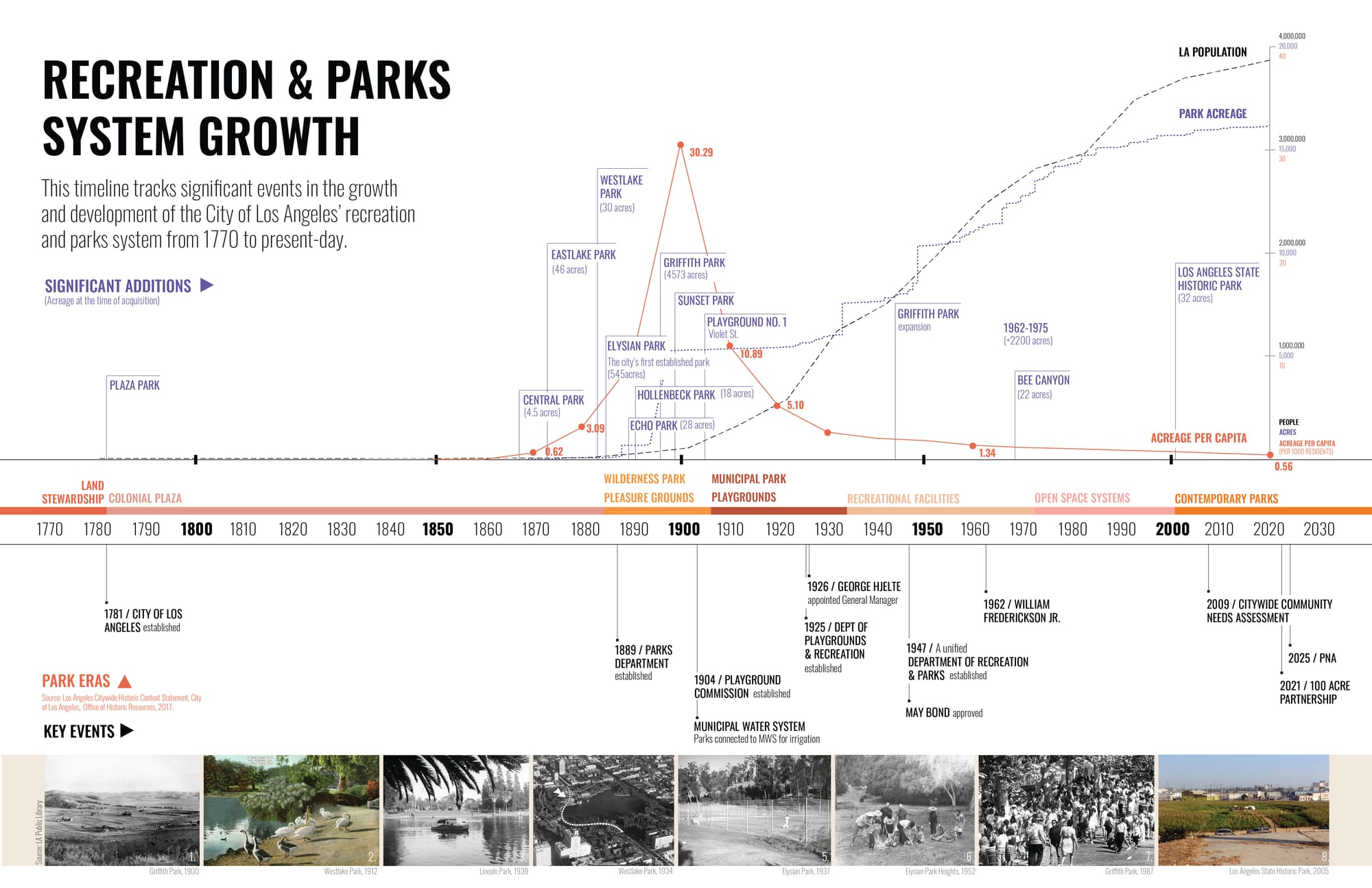

The 496-page document includes a fascinating history of LA's park system — go ahead, shed a few tears for the 1930 Olmsted-Bartholomew Plan known as the "emerald necklace" which proposed 71,000 acres of parkland that never materialized — a breakdown of park use by region, and a rigorous analysis of what's working in peer cities. I also appreciate how this document establishes brand-new department-wide classifications of existing parks based on function and size — mini-park, neighborhood park, canyon park, linear park, etc. — as well as standardization for features and amenities, including how the park should connect to the surrounding community. Just having this shared language will be so helpful for Angelenos to advocate for what kind of parks they want to see in their neighborhoods.

But most importantly, LA's Park Needs Assessment provides a roadmap — or perhaps a well-shaded, native-planted pathmap? — for a department that's been asked to do more and more with less: proposing new funding solutions, targeting immediate interventions, and guiding park growth for the next generation or more.

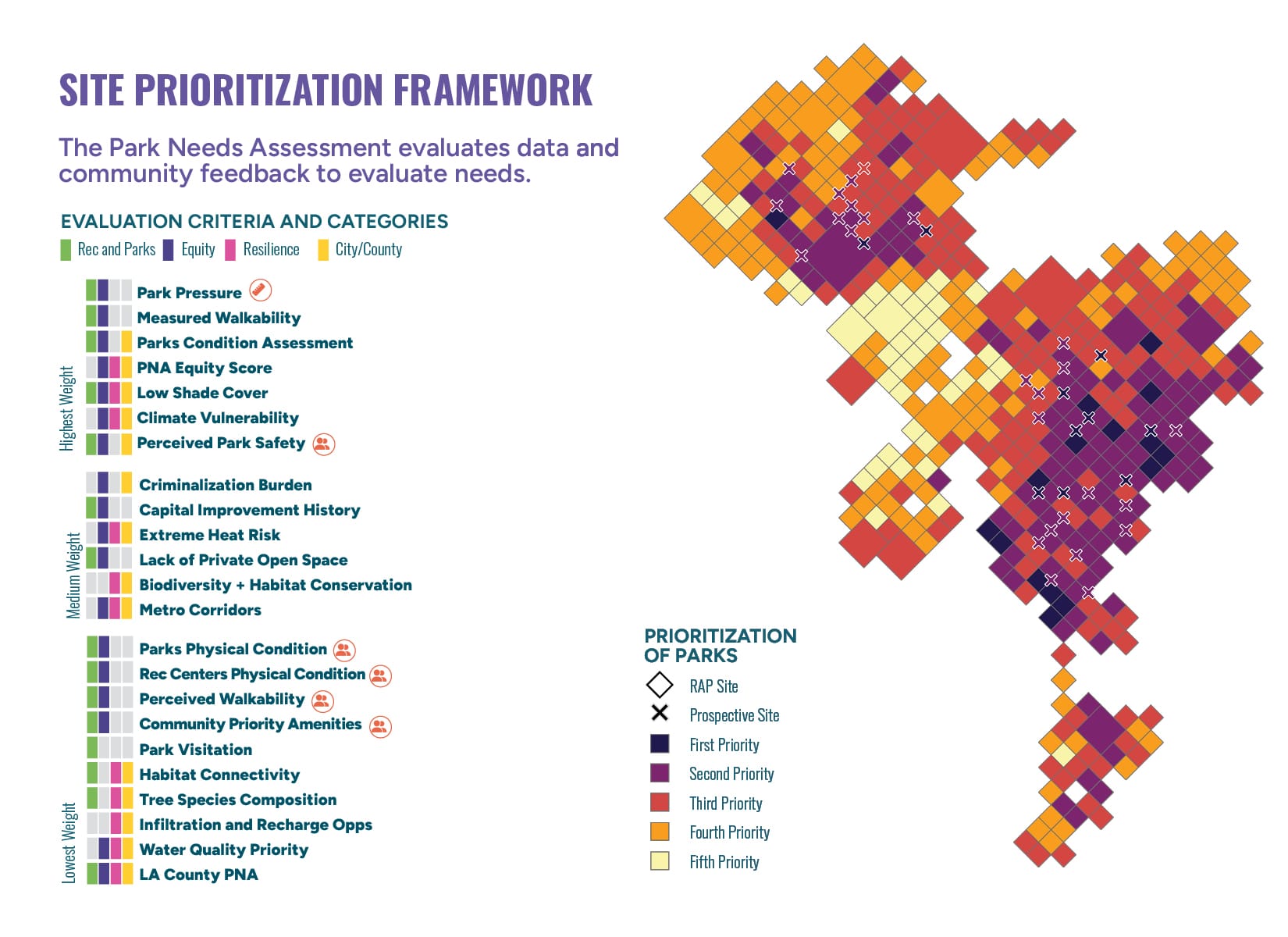

"It will help us as a department to really develop a decision-making framework," says Kim. "It also ensures that we're putting our investments in the right places."

I've written a lot about LA's plummeting public-space status; we recently dropped to 90th out of 100 U.S. cities in the Trust for Public Land's annual ParkScore index. One reason our rankings are tanking is access: nearly 1.5 million Angelenos — more than a third of LA residents — do not live within a 10-minute walk of a park. But what I didn't understand until I spoke with Jessica Henson, a partner at OLIN who presented at many of the outreach meetings, is how not having enough parks makes LA's inequities worse. A majority of Angelenos surveyed by the team said they get to parks by driving, which is what you might think is a logical occurrence when you don't have a park within walking distance. But what's actually happening, Henson says, is that Angelenos in the most high-need areas are choosing parks farther away from their home — and often not in the city of LA — because they feel cleaner, safer, or more well-maintained. "People will drive across LA to use a 'good park.' If the park in their neighborhood was better or more accessible, we could reduce pressure on other parks and reduce driving," she says. "The collective benefit for all parks being improved, not just the ones in privileged communities, puts less pressure on city resources. Better parks in more communities is better for all communities."

That's the city we want: where everyone can walk to multiple, high-quality public spaces. But we haven't created enough of them to keep up with the demand.

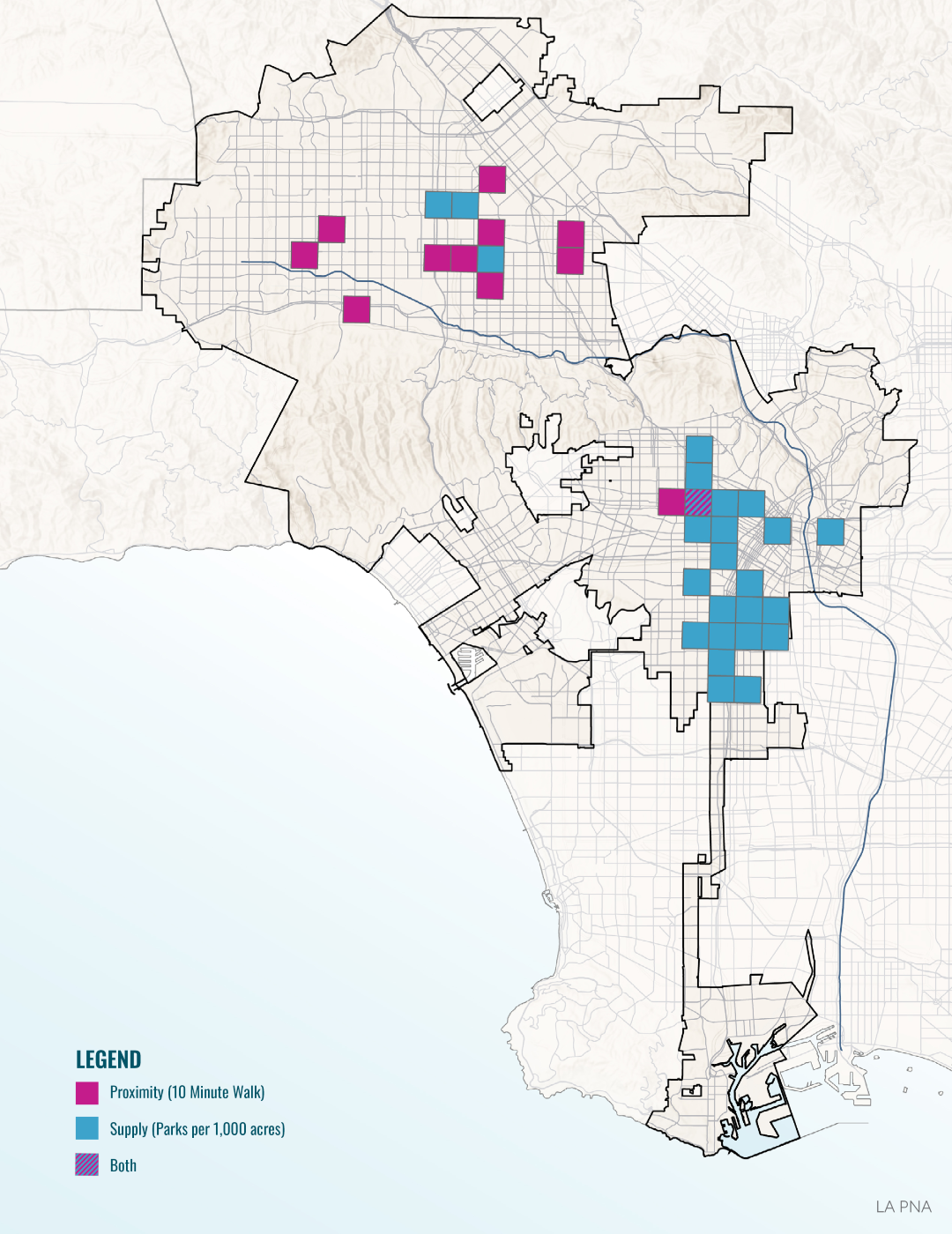

LA clearly needs new parks. Lots of them. And to target exactly where those new parks should go, the needs assessment uses the PerSquareMile tool, an exciting new site prioritization resource developed by GreenInfo Network and the UCLA Institute of the Environment and Sustainability. The tool divides the city up into square-mile increments and uses a wide range of criteria to evaluate park need within each square, says Jon Christensen, adjunct assistant professor at UCLA Institute of the Environment and Sustainability. "The PerSquareMile tool easily enables us to identify the places where new park space would serve the most people who currently don't have a park within walking distance of their homes or who live in densely populated neighborhoods that don't have enough park space for the number of people living there."

But the real beauty of the PerSquareMile tool is that once you've carved the city up into square-mile grid cells, it's very easy to see where just a handful of parks can provide an outsized benefit. "We used the PerSquareMile tool to find places where 12 new park spaces could provide a park within walking distance for around 86,000 residents, and 25 places where new park space could alleviate park pressure for around 500,000 residents," says Christensen. "That's a manageable number."

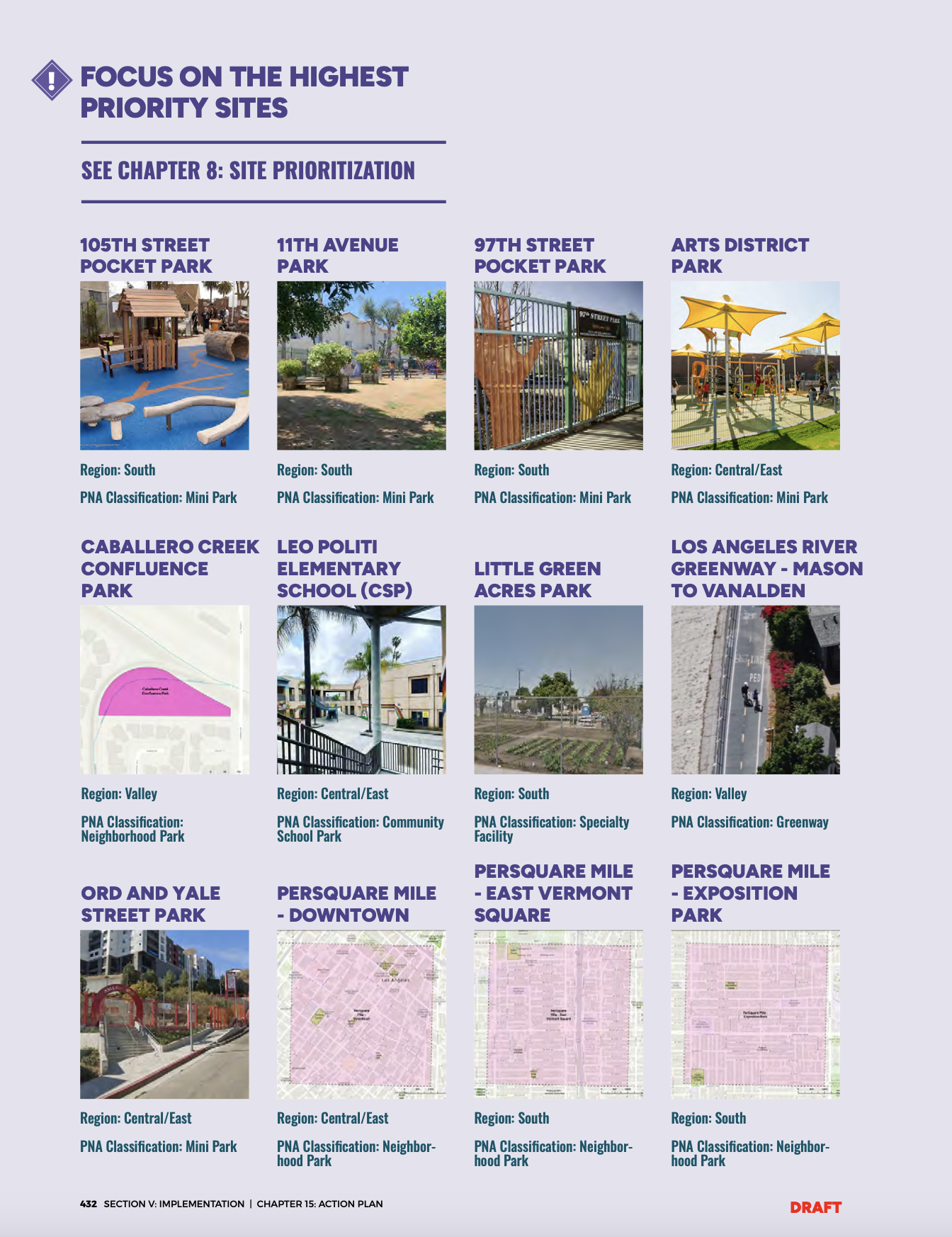

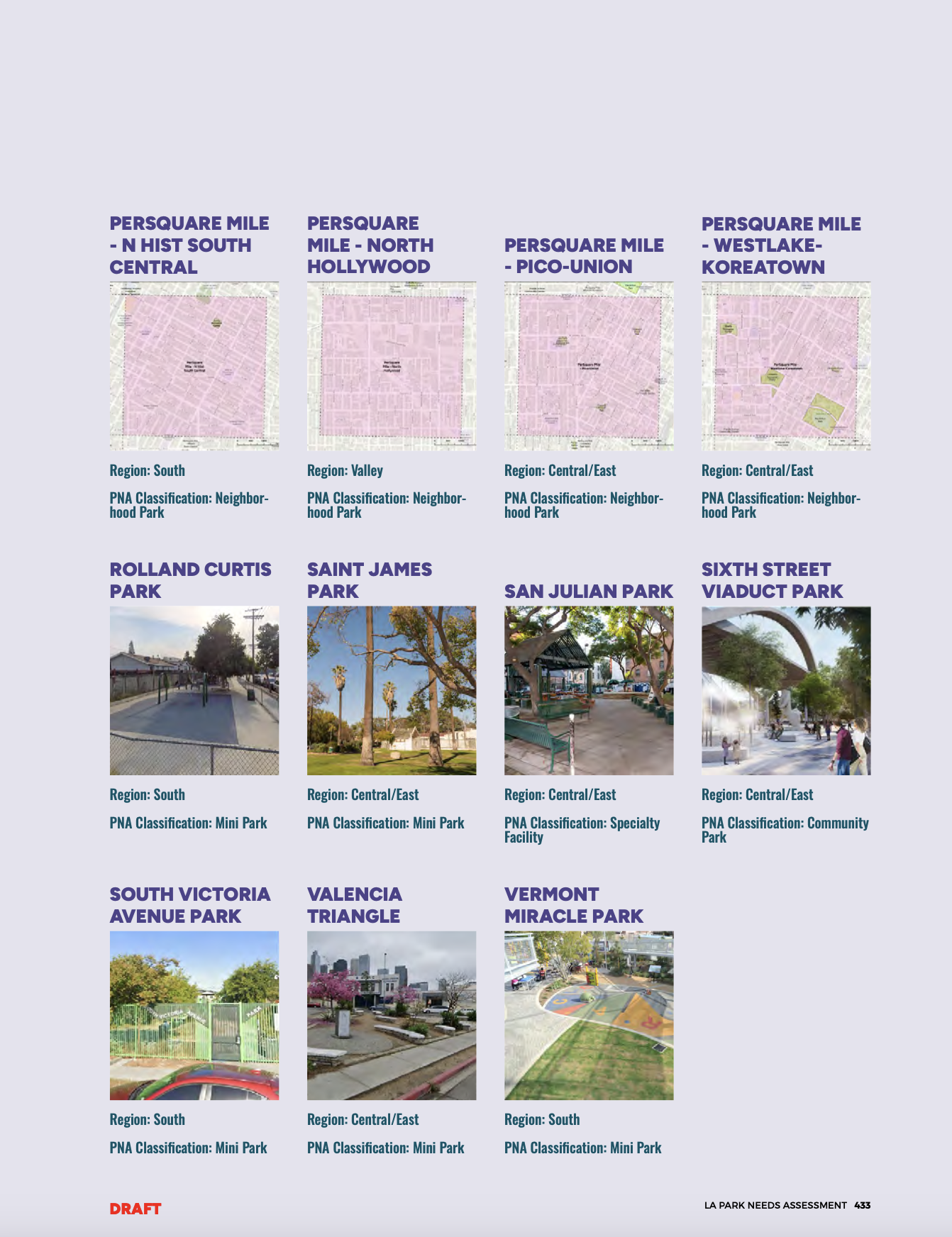

Using the PerSquareMile tool combined with their own evaluation system also helped the team highlight where existing park sites could be improved, expanded, or reconfigured to better serve their communities. The recommendations list 23 parks, including seven proposed parks, as the highest priority sites.

Acquiring new park property, as I noted earlier, has historically proven difficult for LA. But even though the team identified existing public land each of those proposed park areas, there's least one park just waiting to be developed in every single high-need grid cell — an LAUSD schoolyard. Last week LAUSD's board unanimously voted to approve a long-awaited joint-powers agreement with the city to operate parks on campuses. This new agreement means LA no longer needs to go through a separate permitting process for each new school it adds, says Councilmember Nithya Raman, who has been spearheading the city's Community School Parks program. "This program enables us to quickly bring recreational space to neighborhoods that lack such facilities, providing safe play spaces for thousands of children and their families." What it won't do, unfortunately, is speed up the LAUSD greening projects being held hostage by an uncooperative facilities department. The joint-powers agreement needs to find new ways to collaboratively green and open schools. Because as I wrote last year, "while opening a schoolyard as a park is important for access, it doesn't address the bigger problem: most LAUSD schoolyards don't resemble parks at all."

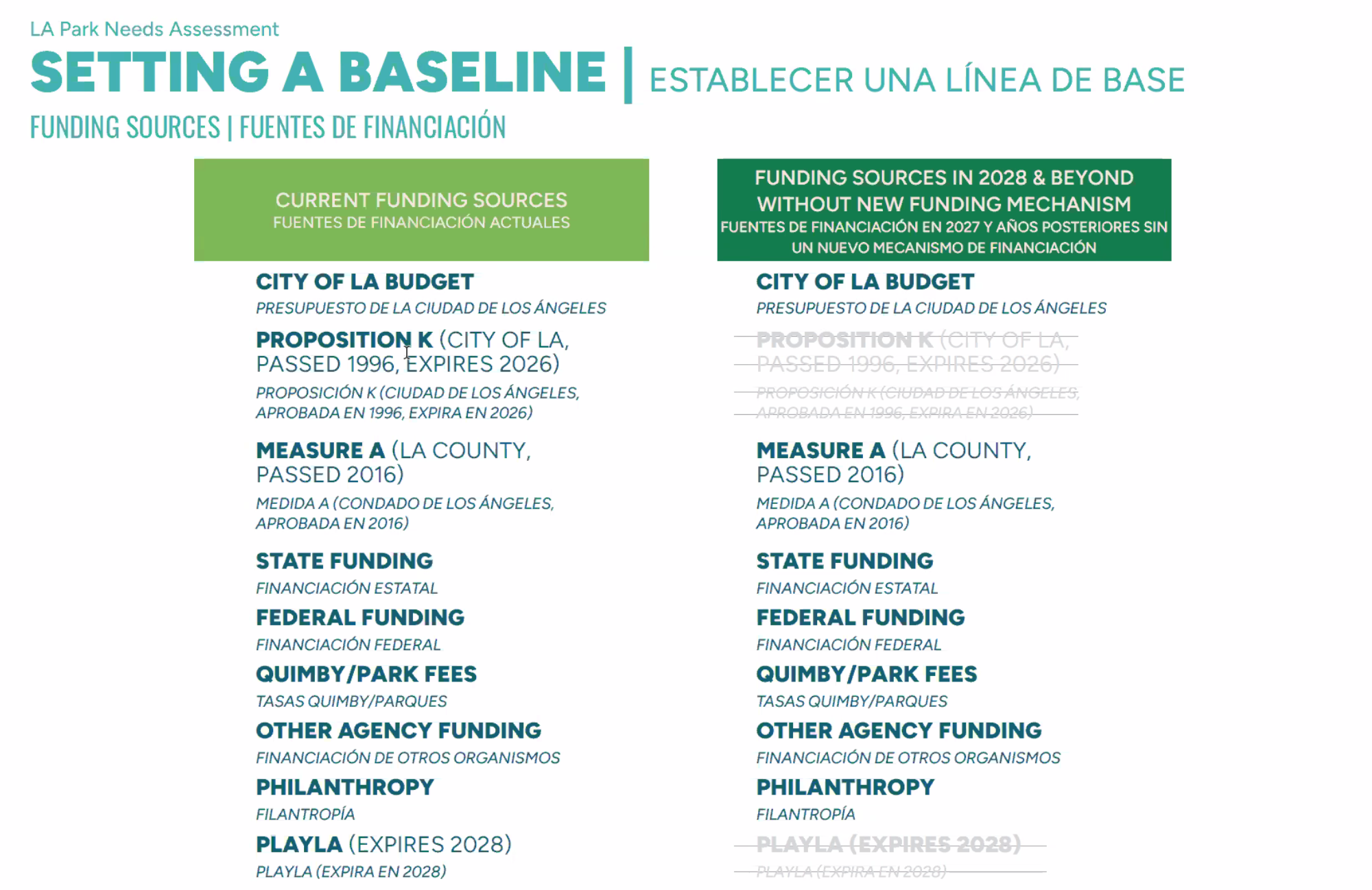

Of course, a city with a billion-dollar budget hole can't pay for any of this, and the funding strategies proposed by the needs assessment are already too late to prevent a gap. Proposition K, which LA city voters passed in 1996, sunsets next year, and the city will either need to levy a new special assessment on property taxes or come up with another way to raise money. There are other sources that we need to talk seriously about as well: the role of private partnerships and philanthropy as park stewards, which I wrote about earlier this year, and the largely untapped potential of earned revenue, which I will examine in depth in a future newsletter. And a reminder that even though LA28 is trying to position its $160 million for youth sports as a legacy investment, PlayLA sunsets in 2028 as well, potentially leaving a massive programming vaccum across the city.

After watching this process play out over the last few months, it's clear there are no quick fixes. "This is a generational, systemic problem — you can’t solve it in five years," says Connie Chung, managing partner at HR&A Advisors, and a member of the needs assessment team. "How do we make this the roadmap that continues to be fresh and adaptable for 10 years or longer?" Which is why LA's structural park-funding problems also need to be addressed as part of the city's ongoing charter reform conversations. While the city's overall operating budget grew by 68 percent from 2009 to 2023, the parks department's budget grew by only 35 percent over the same time period. This is, in part, because of the charter-mandated amount of LA city property tax revenue we allocate to parks: .0325%, yes, only 3.25¢ per $100 of assessed property value goes to the Department of Recreation and Parks, A PERCENTAGE THAT HAS NOT CHANGED SINCE 1937. In comparison, the library's allocation was increased from .0175% to .03% by voters who approved Measure L in 2011.

Over the next 45 days, the needs assessment recommendations will be finalized and presented to the city's parks commissioners for approval. Then advocates and elected officials will need to work together to shape a potential ask to voters, ideally for the November 2026 ballot. I hope they will look closest at the section of the needs assessment where survey respondents overwhelmingly requested more "unprogrammed green spaces" and "natural areas and wildlife habitats" over any other sports or recreation facilities. Angelenos don't necessarily want pricey park amenities — they want places where they can simply be outside, together. 🔥

🌳 One bright spot for park acquisition is the competitive grants awarded through LA County's Regional Park and Open Space District, which voters created by approving Measure A in 2016; two of these newly acquired parcels are in the city of LA. But we need to think bigger — the city of Glendale bought a former Joann's for $24 million using a $2 million Measure A grant with plans to transform the 2.3-acre property into a park. Turn more box stores into splash pads, please!

🎂 And finally, today is MY BIRTHDAY. Your greatest gift to me is to become a paid subscriber so we can celebrate together on September 20, but remember that you can also make a one-time donation to Torched at any time. I've set the amount to $28, which is also my age. Thank you for your support!