The state of play

Last year, I wrote about how LA's ParkScore had dropped from 80th to 88th out of 100 U.S. cities. This year, I'm sorry to say that we sank even lower — LA is now 90th out of 100.

It was, of all things, a playground that brought together Rick Caruso and Karen Bass for the first time since the fires began. Three months after the Palisades Fire ignited, the frenemies locked arms — symbolically, at least — to announce a plan to repair and reopen the neighborhood's damaged rec center. Standing between them was Lakers coach JJ Redick, whose nonprofit LA Strong Sports was leading the rebuilding effort; Politico's Melanie Mason dubbed the whole scene the "Redick Accords." But there were at least a dozen more partners: architects and engineers from Caruso's Steadfast LA team, local community organizations, and direct financial contributions secured from FireAid, GameTime, and the Banc of California’s wildfire fund. The total support for the playground alone was estimated to be over $1.3 million.

The effort to rebuild the Palisades Recreation Center was touted by Bass as an unprecedented public-private collaboration. When it was his turn to speak, Caruso praised the nimbleness of the private sector in delivering faster results for overburdened public departments. (Although when a playground burnt down across the street from the Grove in 2022, Caruso didn't rush to pay for its replacement. Another of Caruso's frenemies, Television City, did.) But Caruso was generally right. For a city facing such acute fiscal adversity, replacing even a seemingly basic amenity like a playground has become nearly impossible, as Councilmember Traci Park said herself at the event: “For the past two years" — as in, long before the fires — "closing the funding gap to modernize this playground has been one of my top priorities." And that's in one of LA's most highly-resourced neighborhoods. The city's park system clearly needs more help.

The mood was not as upbeat at another parks-related press conference I attended last week. Each year, I await the announcement of the Trust for Public Land's annual ParkScore Index, ranking the country's 100 largest municipal park systems, with a growing sense of existential dread. Last year, I wrote about how LA's ParkScore had dropped from 80th to 88th out of 100 U.S. cities. This year, I'm sorry to say that we sank even lower — LA is now 90th out of 100.

The situation is so bad that TPL commissioned a special report on how to fix LA's problems and — well, I'll let the report, written by Will Klein and Lisa W. Foderaro, share the ugly news:

Los Angeles, one of the world’s great cities and host of the upcoming 2028 Olympics, has one of the most challenged big-city park systems in America. Over the past five years, the City of Los Angeles has plummeted from 49th to 90th in Trust for Public Land’s annual ParkScore ranking of the 100 largest cities in the country.

The cause? A century of disinvestment.

The results? Over 1.5 million Angelenos whose city is depicted with images of lush, rolling ridgelines and sparkling ocean waves yet who lack even a nature path, shaded park, or community swimming pool within a 10-minute walk from home. For one in three residents of the city, nature might be in sight, but it’s profoundly out of reach.

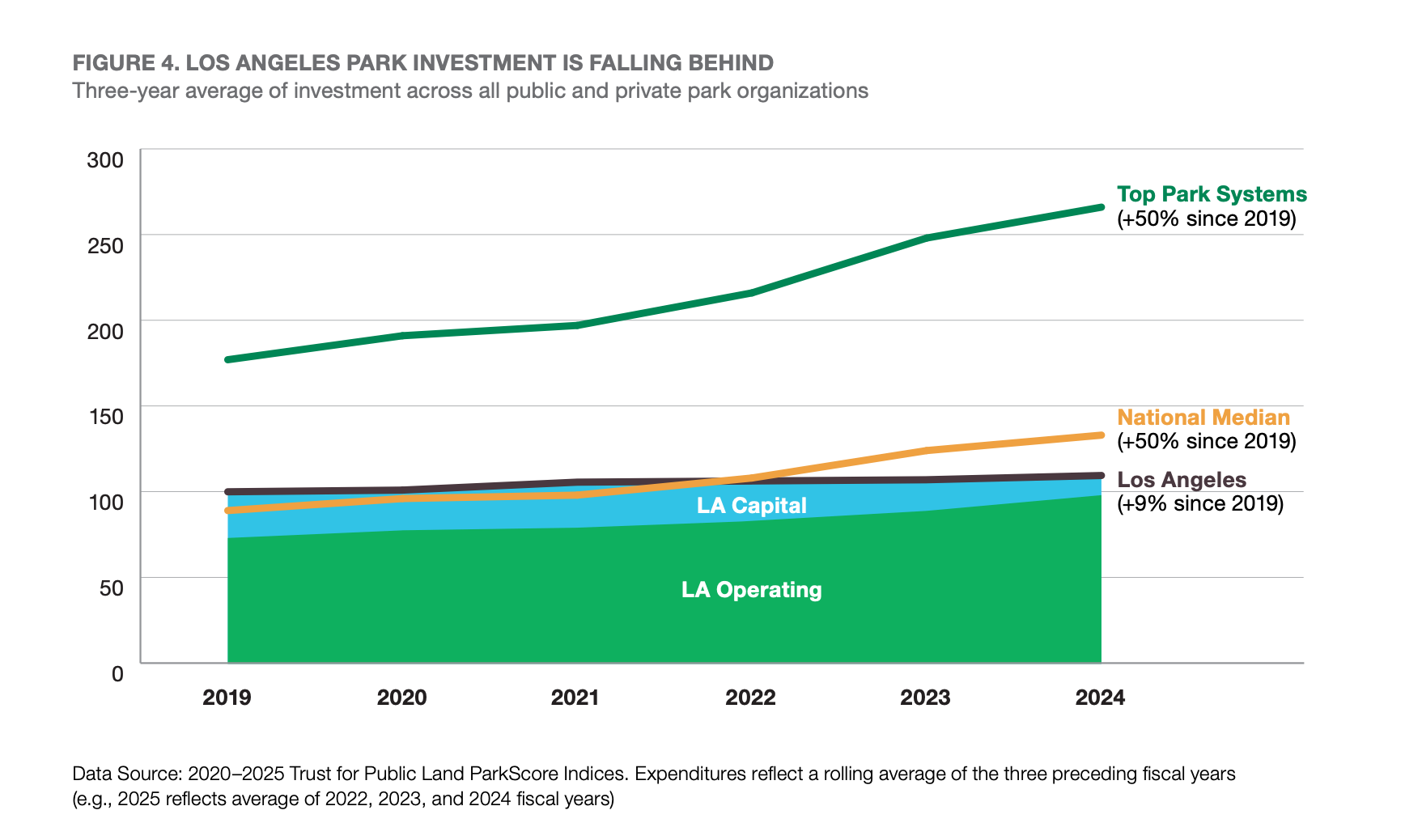

That's quite the gut-punch. But in many ways, the story behind our catastrophic drop is even more troubling. As I wrote last year, our sinking rankings are not necessarily because LA suddenly got so much worse — although we have — it's because, in recent years, other cities have gotten so much better:

For most Americans, local parks are the nearest "outdoors." In the five years since the pandemic began, big cities across the country have doubled down on their park systems, in many cases increasing and accelerating their investments in these need-to-have resources. Los Angeles wasn’t among them.

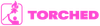

Allowing our park system to effectively collapse is certainly a bad look for a city set to host the largest sporting events in the world. But what should really be haunting LA officials are the comparisons to our peer cities — even comparisons to cities we don't necessarily consider to be peers; Irvine shot up to #2. And the data in this report doesn't lie: many of the challenges facing LA right now would be vastly improved if we could simply raise that ParkScore rating. Particularly when it comes to rebuilding our social infrastructure citywide after the fires.

Torched readers know that the state of LA's parks is not to be blamed on Recreation and Parks staff. This is a political choice made by LA’s leaders. Our current park-funding mechanism, Proposition K, expires next year and we don't yet have a plan to replace it. During this month's budget discussions, councilmembers noted that a parks needs assessment is underway — the first since 2006; again, political choice! — and the goal is to put a new Proposition K on the ballot next year. (There will be a gap, but better late than never.) Going back to voters to re-up K is going to be a daunting task, but it also can't possibly cover this yawning financial chasm alone. As the TPL report notes, the current flow of Proposition K dollars "only covered about a quarter of the requested maintenance needs across its 100 completed projects" in 2024. That simply isn't enough money to update the city's parks, let alone maintain them.

Let's just take playgrounds, since that's the topic of this newsletter. Over the last ten years — exactly as long as I've had children — I've noticed the state of our playgrounds deteriorate most precipitously over the last few years: outdated equipment, missing swings, the mats beneath them crumbling into rubberized dust. (Some playgrounds still have sand, which is an accessibility violation.) The TPL ParkScore rankings have aggregate figures for the number of playgrounds per resident — LA has 4.99 playgrounds per 10,000 children; top cities have 23 playgrounds per 10,000 children. But thanks to LA's park needs assessment, we now have ratings for every single park amenity in the entire system. This has confirmed my kids' own assessments of the playgrounds we visit: not only are there not enough of them, the ones we use regularly are rated fair or poor.

Sometimes councilmembers manage to scrape together enough funding to replace playgrounds, but if and when these structures are damaged or vandalized, fixes are slow. The way it works currently, officials only seem to respond to a catastrophic event, leading one to conclude that the fastest way to get new playground installed in this city is by burning the old playground down.

If we want to build a park system that's as strong and resilient as our would-be peers, the report recommends that a sizable chunk of the support — financial and otherwise — needs to come from elsewhere in the city. Right now, it doesn't:

There is significant untapped leadership and investment from other public land managers and the philanthropic sector in Los Angeles. A paltry six percent of the city’s total park investment comes from philanthropic organizations or other public agencies. (That is half the national average of 12 percent.)

And that's basically the key recommendation of the report: pursue creative partnerships. One of those partnerships is already underway. Greening and opening schoolyards with LAUSD is one TPL-recommended intervention I wrote about last year. A total of 10 community school parks have been opened and are operating on the weekend. TPL is now working with LAUSD to green and open 28 schoolyards by 2028 — more on that plan soon. But LA needs a strategy that's much more comprehensive. The report recommends following the example of the Austin Park Foundation, which manages an adopt-a-park program with dozens of community partners. It's funded, in part, by the Austin City Limits music festival. What's that again? Large citywide events that will greatly impact the ability of local residents to access public space are coordinating ongoing park improvements and maintenance as a legacy intervention? Say more.

LA does do something like this now, but in a limited, and not necessarily equitable, way. Only five parks out of 450 have been adopted by foundations or corporations through the Los Angeles Parks Foundation program. About 100 parks have "friends of" nonprofits that take donations. Some LA city parks — but not all of them — have Park Advisory Boards formed by city staff and community members. Local professional sports teams sometimes chip in for improvements, and nonprofits also play a role. In Historic Filipinotown, Unidad Park — the photo at the top of this story — recently received a thoughtful refresh thanks to the Los Angeles Neighborhood Land Trust, which works to acquire land and act as a caretaker for parks all over LA County. LANLT also keeps a watchful eye on Unidad Park in particular; their offices are right across the street. The reason you might not have noticed a funding disparity at your local park is because you may already have one of these partnerships in place. But the majority of LA's parks don't.

Of course, it shouldn't take a nonprofit intervention or a check from a private foundation just to make basic park fixes. But with all eyes on LA, this is our one and only opportunity to leverage our moment in the global spotlight. We really do need to get creative; put a toilet-minded JJ Redick in charge of the all the park bathrooms!

LA needs engaged, well-endowed partnerships for all its parks — the type of partnerships that Bass and Caruso claimed they championed, together. Rebuilding the Palisades rec center with this dream team could become the gold standard for how to rebuild parks all over LA. When it's finished, these families will play at the nicest playground in the city, by far. And it should be that way; they've lost everything. But as the Palisades receives the world-class park facility that every LA community deserves, the chance that any other LA neighborhood will see similar investments being made for their kids is dwindling year after year. 🔥

📝 Do not forget to take the city's park needs assessment survey — I had both my kids take the survey as well! The second round of in-person meetings are underway, or you can watch the recording of the virtual meeting

⚖️ Last year I wrote about another challenge facing LA's parks: a class-action lawsuit filed on behalf of four plaintiffs with mobility disabilities who have been "denied full and equal access to its parks and park facilities." The class notice has now been posted

📺 And finally, welcome John Mulaney fans! If you missed me on Everybody's Live with John Mulaney, you can watch it on Netflix, check out my photos, or share this very entertaining clip. And also thank you to Bethy Squires at Vulture and Doug Gordon at Streetsblog for the thoughtful reviews of the episode. Just for this week: take $10 off an annual subscription to Torched and share this deal with others!