Made in the shade

"We're trying to change the way that we as Angelenos think about our neighborhoods, so that we actually look around and say, where can there be more shade — in the same way that many of us have thought about trees"

Monica Dean and Edith de Guzman started fielding the question last summer. As longtime members of the local urban forestry community working to cool a scorching city, their colleagues kept approaching them, wondering how a looming deadline might spur local leaders to take more dramatic action. The refrain was urgent, insistent, and very familiar to Torched readers: What's the shade plan for the Olympics?

Dean and de Guzman realized they were in a unique position. In their academic roles — Dean is the climate and sustainability practice director at USC Dornsife Public Exchange, and de Guzman is a water and adaptation policy cooperative extension specialist at UCLA's Luskin Center for Innovation — they were part of a growing field of researchers raising the alarm about extreme heat, but weren't beholden to the agenda of a specific city or county. It gave them a window to turn practice into policy, Dean says. "How can we use the data, and science, and tree-planting maps where we know, down to the city block level, where there are open tree wells, to connect people in a way that's going to provide the biggest benefit for the community — both for the games, but also for the long-term legacy?"

The result is ShadeLA, a brand-new initiative launching today that's using the timeline of upcoming megaevents to foster an unprecedented collaboration across the environmental agencies, community groups, and nonprofits that are already cooling and greening LA County. The effort counts a long list of participating entities, including the city of Los Angeles, LA County's Chief Sustainability Office, Metro, and, yes, LA28 — which has yet to reveal its own sustainability strategy for 2028 but, in the meantime, has also endorsed this plan outright.

While filling LA's empty tree wells is important — there are about 250,000 vacant ones just in the city of LA — de Guzman would like Angelenos to start thinking more broadly about shady solutions. "We're tethering this to shade because the science is now here to unequivocally tell us that, in an outdoor context, this is the slam-dunk way to alleviate discomfort and prevent heat-related illness, and also, ultimately, death," she says. And that's why ShadeLA's aspirations are going far beyond tree-planting, Dean says. "Trees, as much as we love them for all of their co-benefits, can't grow everywhere. Sometimes there's physical constraints. So it's really not enough for us to just plant trees. We also have to add shade sails, and awnings on businesses, and umbrellas."

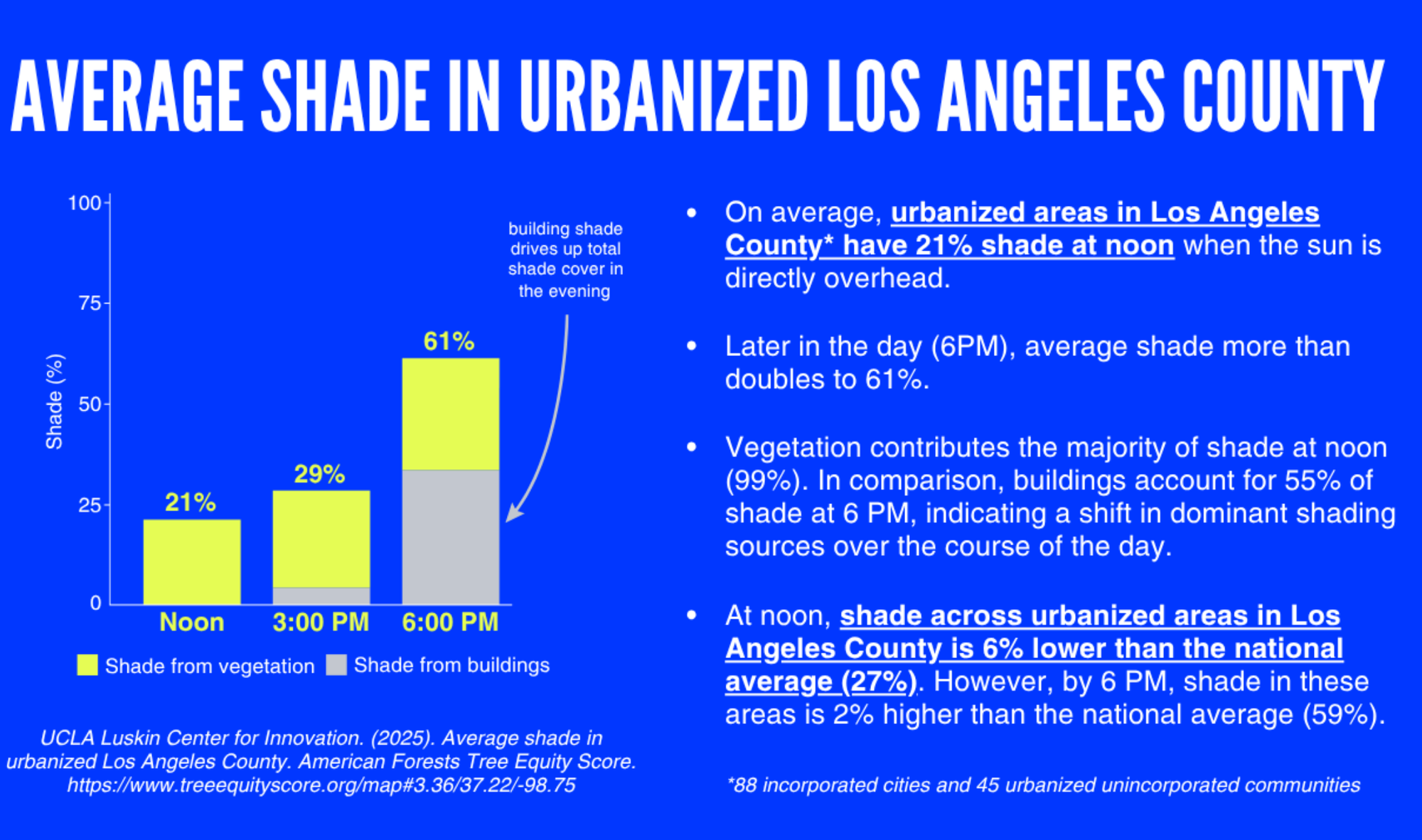

To truly cool the city down, depaving LA needs to be just as much of a priority as shading LA. We need more of the space that's devoted to steering and storing cars to be busted up for bioswales and pollinator corridors. But for the hottest communities at the hottest times of day, the research shows that engineered shade is a highly cost-efficient tool. The nifty new National Shade Map, developed by V. Kelly Turner for the UCLA Luskin Center for Innovation — her about-to-launch Center for Heat Resilient Communities was defunded by NOAA cuts — now allows Angelenos to measure shade by census district, toggling between the differences at noon, 3 p.m., and 6 p.m. to see how tree canopy and buildings work together. Just poking around the map, it's clear that one very effective way to quickly shade more of LA's streets and sidewalks would be to simply build many more tall buildings, preferably ones that are full of housing. And that's absolutely the kind of conversation that ShadeLA wants to start, says de Guzman. "We're trying to change the way that we as Angelenos think about our neighborhoods, so that we actually look around and say, where can there be more shade — in the same way that many of us have thought about trees. How can we be stewards of that civic resource?"

LA does still need to plant hundreds of thousands of trees, and Dean and de Guzman say there is plenty of precedent for getting them in the ground within the three-year timeframe we have before us. Before the 1932 games, up to 40,000 palms — don't you dare call them trees — were planted along LA streets in the midst of the Depression, although there's disagreement over whether the planting was for the Olympics or a well-timed Works Progress Administration effort. Ahead of the 1984 games, LA was combatting a smog crisis so dire that when the Clean Air Act was passed, it was determined that LA would need one million trees planted to be in compliance with air quality regulations. Once again facing a recession that had decimated city resources, an enterprising young environmentalist named Andy Lipkis rallied volunteers to plant one million trees through his nonprofit, TreePeople. (I wrote about this in May, including the must-watch NBC segment.) The trees were indeed planted and plotted on a map, although, like the majority of LA's urban canopy, those trees are mostly on private property, not shading the public realm.

Dean and de Guzman are reluctant to tether ShadeLA to specific tree-planting goals, which historically have not necessarily resulted in more equitable outcomes. (I'm still seeing freshly planted trees die in my neighborhood, not to mention all the dead trees the city is in no hurry to remove.) But they do have a new way to measure progress. While green, living, biodiverse shade is clearly the priority, Dean and de Guzman would like Angelenos to start looking at their community with ideas for how to increase the overall units of shade, coming up with new and creative ways to convey the personality of their neighborhood. I vote for more colorful awnings, canopies, and arcades, just like the old days.

As someone who tried to get a few parkway trees planted in the empty wells around our baked-asphalt elementary schoolyard, only to have the city, a local tree-planting nonprofit, and LAUSD all pointing fingers at each other like the Spiderman meme (and they're still not planted!) my concerns with any volunteer-driven approach to extreme heat remain the same. Shade shouldn't be opt-in, and the longer we refuse to treat tree maintenance like actual municipal infrastructure, I fear the only progress will be made in affluent neighborhoods. But in the face of so much adversity — no funding, no staffing, our ongoing federal occupation — LA needs more unified, thoughtful, sustained efforts like this to combat longstanding injustices through community care. What Dean and de Guzman are really envisioning is a kind of mutual aid for shade. 🔥

☂️ The ultimate shady resource is finally here: Shade: The Promise of a Forgotten Natural Resource is out next week! Join me for a Torched Talks with author Sam Bloch on Wednesday, August 6 at 12 p.m.